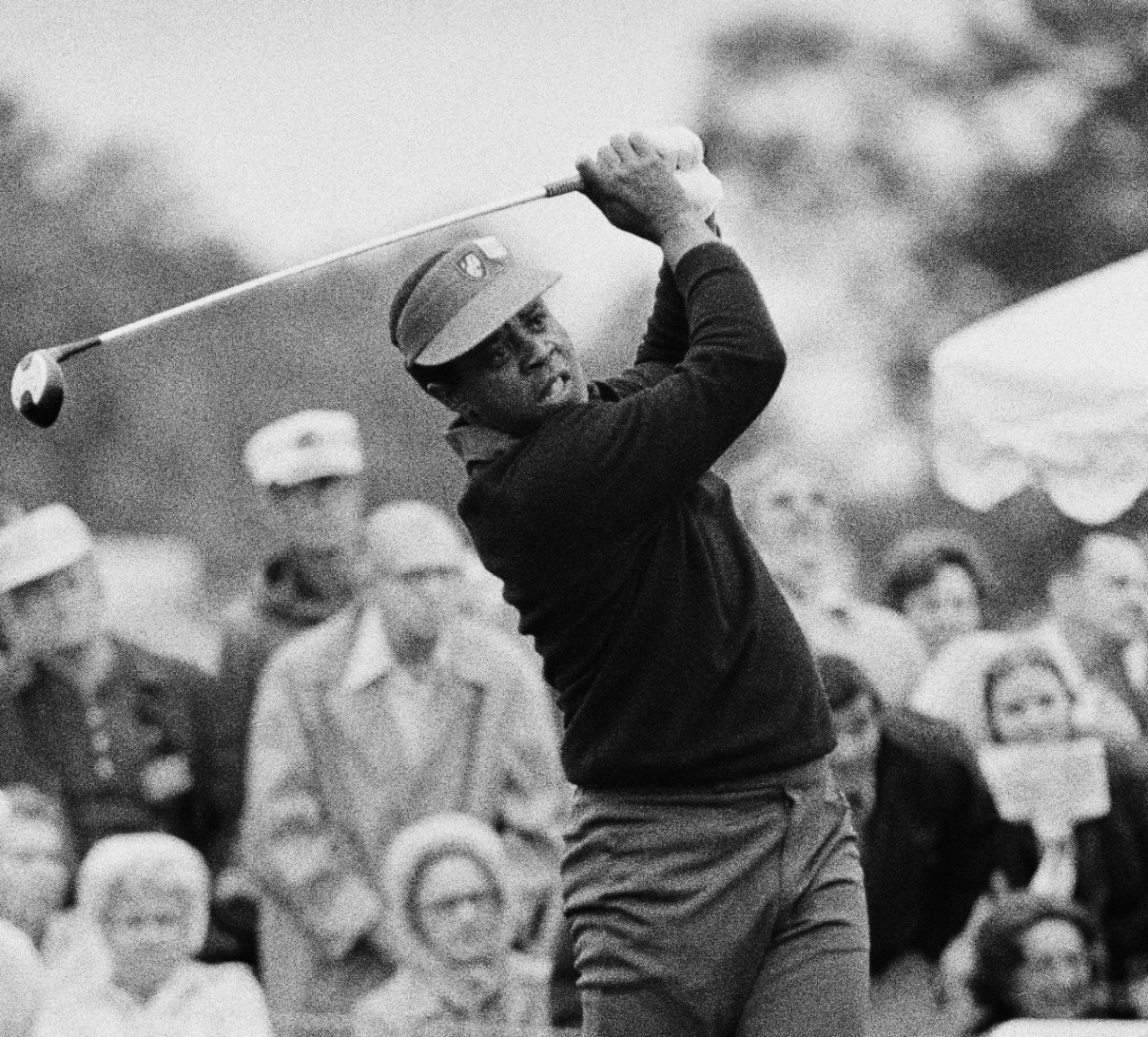

Staying the course: How Lee Elder persevered in golf and in life

Nearly 50 years after Lee Elder became the first Black player to qualify for and play in the Masters Tournament, the trailblazer will take his first turn as an honorary starter for this year’s competition. And while much has changed since Elder, 86, first teed off at Augusta National in 1975, many of the challenges he faced playing the game remain the same for Black golfers today.

“It’s just such an emotional thing to think about — how I, a little Black kid from a Dallas ghetto, was able to rise to the heights of playing in the most prestigious golf tournament in the world,” Elder said.

“I’m proud to have been selected as an honorary starter this year because I feel it’s something that is going to help young BIPOC golfers. Seeing a Black person on the course at the Masters is certainly going to enhance their thought of getting involved in the game.”

Lee Elder

According to the National Golf Foundation, Black players make up just 3 percent of recreational golfers and 1.5 percent of competitive golfers. Though low, these participation figures still top those of Elder’s era, when lack of access, prejudicial regulations, and threats to personal safety kept Black players out of the game. Elder’s journey helped advance the game, ultimately inspiring golf enthusiast Stephen Curry to support the next generation of BIPOC golfers though Curry Brand powered by Under Armour.

“Lee Elder is legendary. He has spent his entire life breaking down golf’s color barrier, paving the way for future BIPOC golfers both on and off the course,” said Curry. “When I began building Curry Brand, I knew I wanted Lee to be a part of the family, and I’m humbled to be working with him promoting equality in golf and changing the game for good.”

Growing up, Elder faced several hurdles when pursuing his passion for golf. His brother Raymond introduced him to the game, and the duo caddied at Tenison Park Golf Course, just a few miles from downtown Dallas. However, Elder could not play on the same course at which he worked — the nearest course that allowed Black players was about 30 miles north, and only open on Mondays. The passing of both of his parents eventually forced Elder to move to Los Angeles at age 10 to live with his aunt, where a 20-minute bus ride could get him within a block of a golf course for Black players.

“At the time, a lot of the minority players who wanted to pursue golf lived a great distance from the courses that they were able to play on. It was difficult for them to get to these courses, and even more difficult to carry their clubs along the way,” Elder said.

“It was a hard road, and if I had not gone to the Los Angeles area, I don’t think I would have been able to continue working at the game. It would have been almost impossible in Texas, or anywhere in the South, because it was just a tough time for minority players.”

Lee Elder

Golf’s segregation, including the PGA Tour’s Caucasian-only rule that lasted until 1961, led to the development of the United Golfers Association, an organization that hosted tournaments in which Elder and his fellow BIPOC players could participate. It was at one of these events where Elder met Ted Rhodes, a player widely recognized as the first Black professional golfer. Rhodes saw Elder’s talent and quickly took the young golfer under his wing, coaching him over the course of a decade until Elder earned his PGA Tour card in 1968.

“We traveled for well over a year and a half with Ted playing in tournaments but me just practicing because he felt that if I started to play while trying to get my game together, I would easily go from one bad round to another and get discouraged,” Elder said.

“Ted wanted to make sure that I stayed the course, and ever since, that’s been my motto — once you start something, you have to stay the course to be successful.”

Lee Elder

While Elder incorporated Rhodes’ advice into his game, he also applied it to life on the Tour, refusing to let systemic racism deter him from achieving his goals. In Elder's first year as a PGA player, he had to change clothes in the parking lot of the Pensacola Country Club in Pensacola, Fla., because members would not allow Black players in the clubhouse. In the years that followed, Elder received death threats if he put up a promising performance at a PGA event. Despite these experiences, Elder persevered, and in 1974 won the Monsanto Open — his first professional victory — at the same Pensacola course where he was once denied entry into the club’s facilities. This win made him the first Black player to qualify for the Masters.

Elder played in the 1975 Masters and went on to appear in five more Masters tournaments throughout his career. He was also the first Black player to qualify for and play in the Ryder Cup competition between teams from Europe and the United States, contributing to the winning 1979 U.S. team. Elder ended his career with 16 professional wins, including four on the PGA Tour, eight on the Senior PGA Tour, and four internationally.

In retirement, Elder has made it his mission to support young BIPOC golfers with the Lee Elder Foundation, which aims to break barriers for underprivileged children and adults in golf, business and life. In addition, Augusta National is honoring Elder with two golf scholarships in his name at Paine College, a historically Black college in the Augusta, Ga., area that supported Elder throughout his trips to the Masters. These efforts complement Curry’s commitment to provide six years of funding to the men’s and women’s golf teams at Howard University, another historically Black institution.

When Elder speaks with young golfers today, his advice is simple — sometimes the hardest challenges are the most rewarding.

“I have always said that one of the reasons I took on the challenges of the Tour was because I knew that we had to have someone that would stay the course and help the younger generation that was going to come after us," Elder said. "As long as you too stay the course and continue to work hard at the goal you’ve set for yourself, you will be successful.”

Masters weekend will mark Curry Brand’s expansion beyond basketball gear with the release of the brand’s first golf line on April 9 at UA.com. The Curry Brand collection of men’s apparel and accessories comes on the heels of the fan-favorite UA Range Unlimited Collection launched in collaboration with Curry last summer. Curry Brand will also be donating funds to Ace Kids Golf, an Oakland-based golf program that Elder and Curry partnered to support for the launch of Curry Brand, which will allow the organization to expand its programming to 75 additional Oakland youth in honor of Elder’s accomplishments in 1975.

“Because of the tremendous financial strain of the pandemic, countless recreation centers and programs have been forced to close, leaving local youth with far fewer options for safe, structured fun,” said Preston Pinkney, Director of Ace Kids Golf. “With this donation from Lee Elder, Stephen, and Curry Brand, we can not only support programming for 75 more kids in an effort to bring more equity to the game, but build the next generation of successful athletes both on and off the course.”

More From UA News

MI100: Under Armour and Maro Itoje unveil bespoke boot to mark England centurion milestone

Maro Itoje has collaborated with Under Armour to design a player-exclusive boot celebrating his 100th England cap, a milestone he will reach this weekend at the Allianz Stadium Twickenham against Ireland.

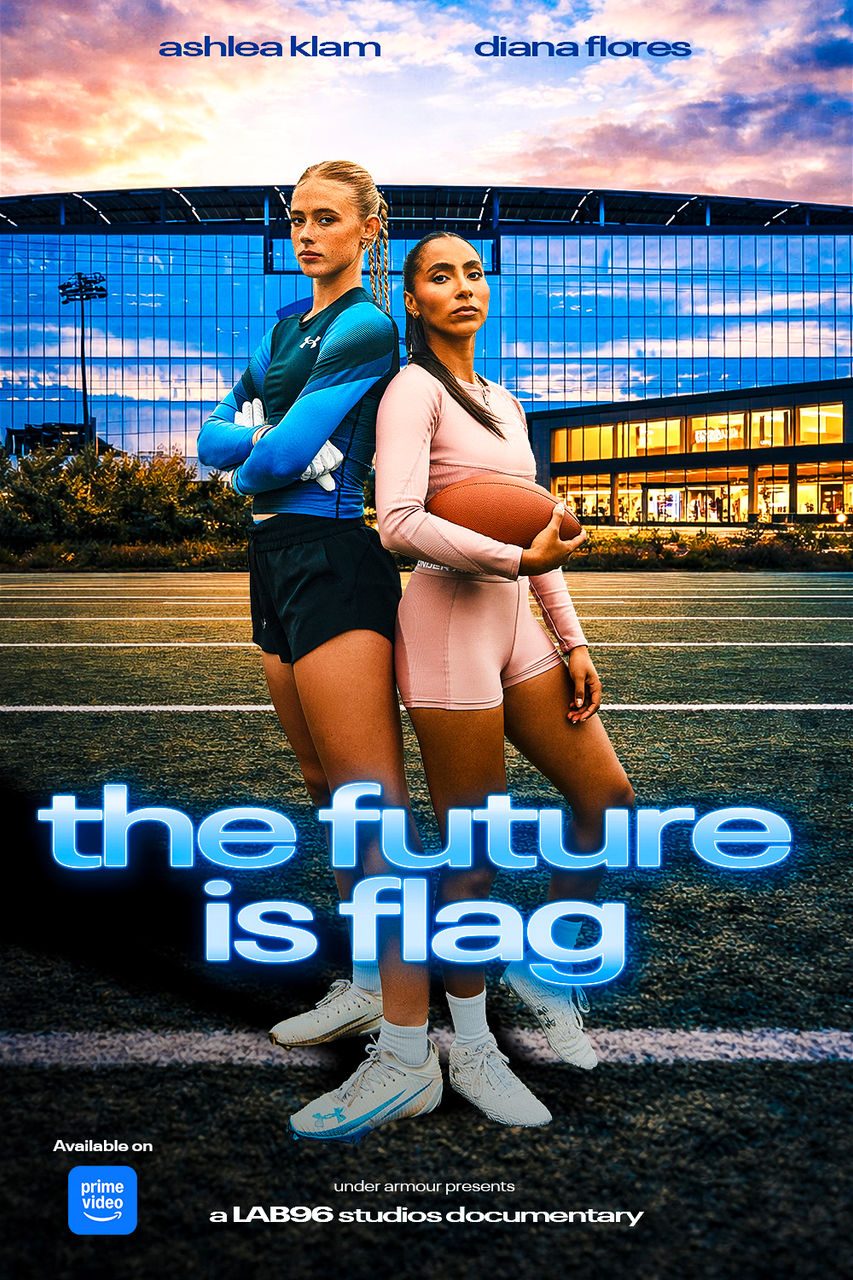

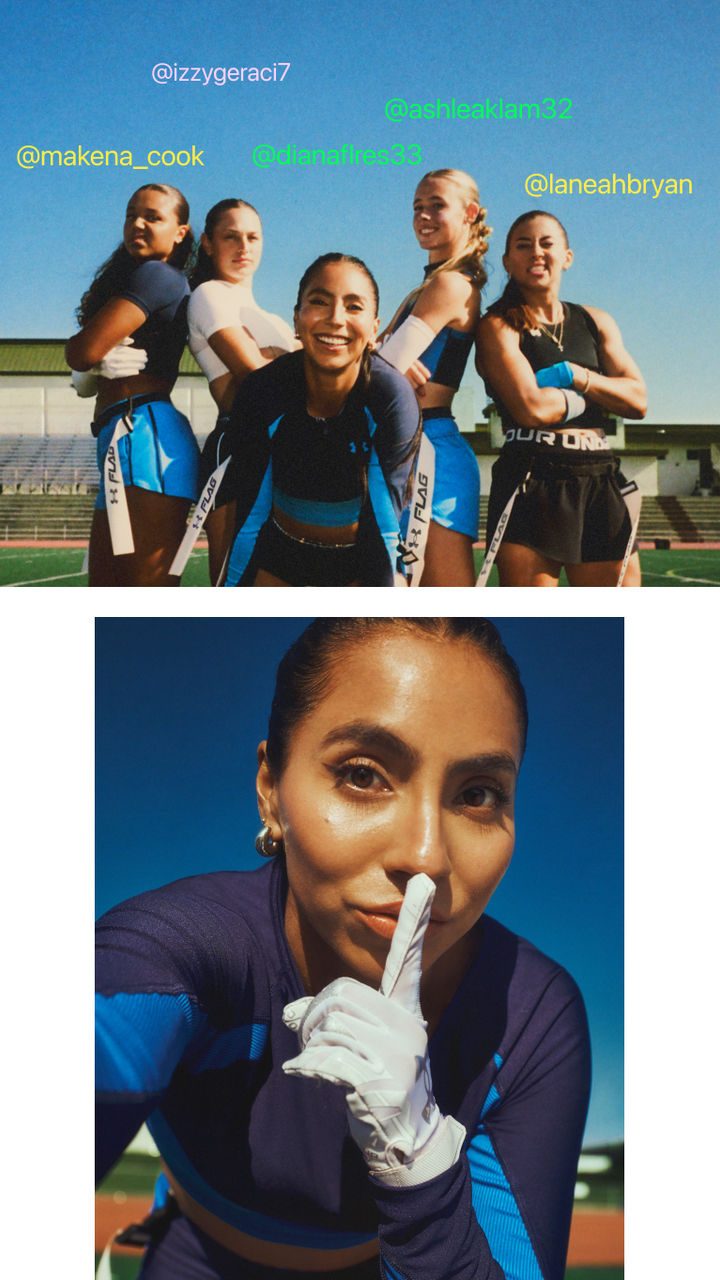

Under Armour’s Lab96 Studios and SMAC Entertainment Highlight the Global Rise of Women’s Flag Football in The Future Is Flag on Prime Video

The Future Is Flag, a definitive documentary exploring the rapid evolution and rising global stakes of women’s flag football. Debuted on Prime Video, the film is directed by filmmaker, showrunner, and executive producer, Monica Medellin (Surf Girls, Prime Video).

Under Armour Drops the Curry 13 - The Final Chapter in a Signature Era

Under Armour today introduces the Curry 13, the final signature sneaker in the Curry Brand lineup and the final chapter of a more than decade-long run of performance innovation built alongside Stephen Curry.

Mikaël Kingsbury Extends His Legacy with Another Podium Finish

The Canadian superstar and the most decorated moguls skier in World Cup history, claimed the silver medal in the men’s moguls event, reinforcing his status as one of the most decorated athletes in freestyle skiing history.

Under Armour Debuts Click Clack: The Next Era, Celebrating the Women Redefining Flag Football

Under Armour Announces $1 Million Grant to Support Girls Flag Football

Under Armour launches its latest women’s baselayer with “LDN Layers” party

Last night, Under Armour unveiled its new Women’s Crop Mock Baselayer by hosting LDN Layers. The evening event brought together all four corners of London in a women-led collective to showcase the versatility of the garment and how it moves effortlessly from training and performance to nightlife and street style.

Under Armour Unveils New Golf Innovations Set to Redefine Fit and Performance on the Course

Under Armour is advancing the next chapter of golf performance footwear and apparel with the introduction of the Drive Pro Clone golf shoes and ArmourDry Polo.

Guangzhou, China - Under Armour Debuts Future Retail Pilot, Fusing Innovation and Community to Redefine the Athlete Experience

Under Armour introduces its first-of-its-kind smart sports community space at Julongwan Taikoo Li in Guangzhou China, marking a pivotal step in its global retail evolution.

Under Armour Welcomes KJ Jackson as Latest Brand Ambassador

Under Armour is proud to welcome KJ Jackson to its growing roster of athletes ahead of his second season with the Savannah Bananas.

Under Armour Partners with the 4Aces GC Ahead of LIV Golf Season Opener

Under Armour is officially joining forces with the 4Aces GC to bring its latest golf innovations to the LIV Golf stage. Outfitting the team set to kick-off their season February 4–7 at Riyadh Golf Club for LIV Golf’s opening event.

Under Armour Honors Legacy at UA Next All-America

Under Armour hosted its 18th annual UA Next All-America Week in Orlando, Florida from December 29, 2025 to January 3, 2026. Empowering 230 of the next generation's top athletes in Football, Flag Football, and Volleyball.

Under Armour and UNLESS Unveil “Pulse,” the Next Chapter in Regenerative Sportswear

Under Armour and UNLESS announce the launch of Pulse, a new regenerative apparel and footwear capsule representing the next chapter in their ongoing collaboration to rethink how sportswear is designed, worn, and returned to the earth.

Meet the Boxerjock Ballbag™

Introducing the Boxerjock Ballbag™ - a breakthrough so supportive, so breathable, so confidence-boosting, it practically gives a pep talk.

EASL and Under Armour Unveil Multi-Year Partnership

This strategic partnership fuels Asia’s premier basketball champions league while also powering EASL Future Champions, creating a unified pathway from rising talent to elite competition.

Under Armour Unveils the No Weigh Duffle Backpack

Under Armour is redefining what a duffle can do with the launch of the No Weigh Duffle Backpack, a lightweight, adaptable bag built for athletes who train, travel, and compete without compromise.

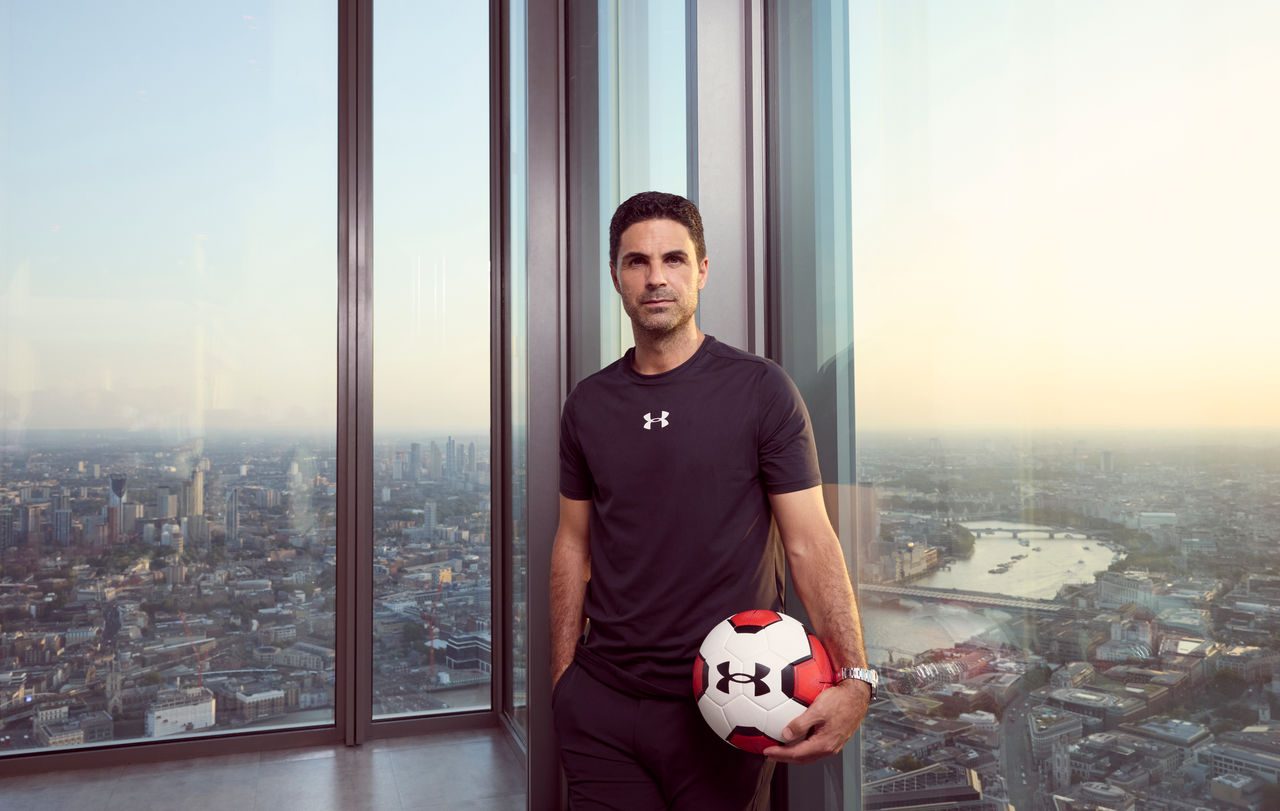

Mikel Arteta and Under Armour Challenge the Next Generation of London’s Athletes

UA Next London may be concluding it’s ninth season of competition, having tested over 12,500 young athletes, but this is a new era for Under Armour’s London athlete program.

IMG Academy Set to Host Inaugural 2026 Under Armour Track and Field Nationals

Under Armour and IMG Academy are proud to announce the inaugural 2026 Under Armour Track & Field Nationals, coming this spring to the IMG Academy campus—aimed at elevating youth athletics a premier destination for elite athlete events.

UW Athletics and Under Armour Extend Landmark Partnership

University of Wisconsin-Madison and Under Armour announced a 10-year extension of its current partnership, reaffirming a relationship built on innovation, performance, and a shared commitment to elevating the university’s student athletes.

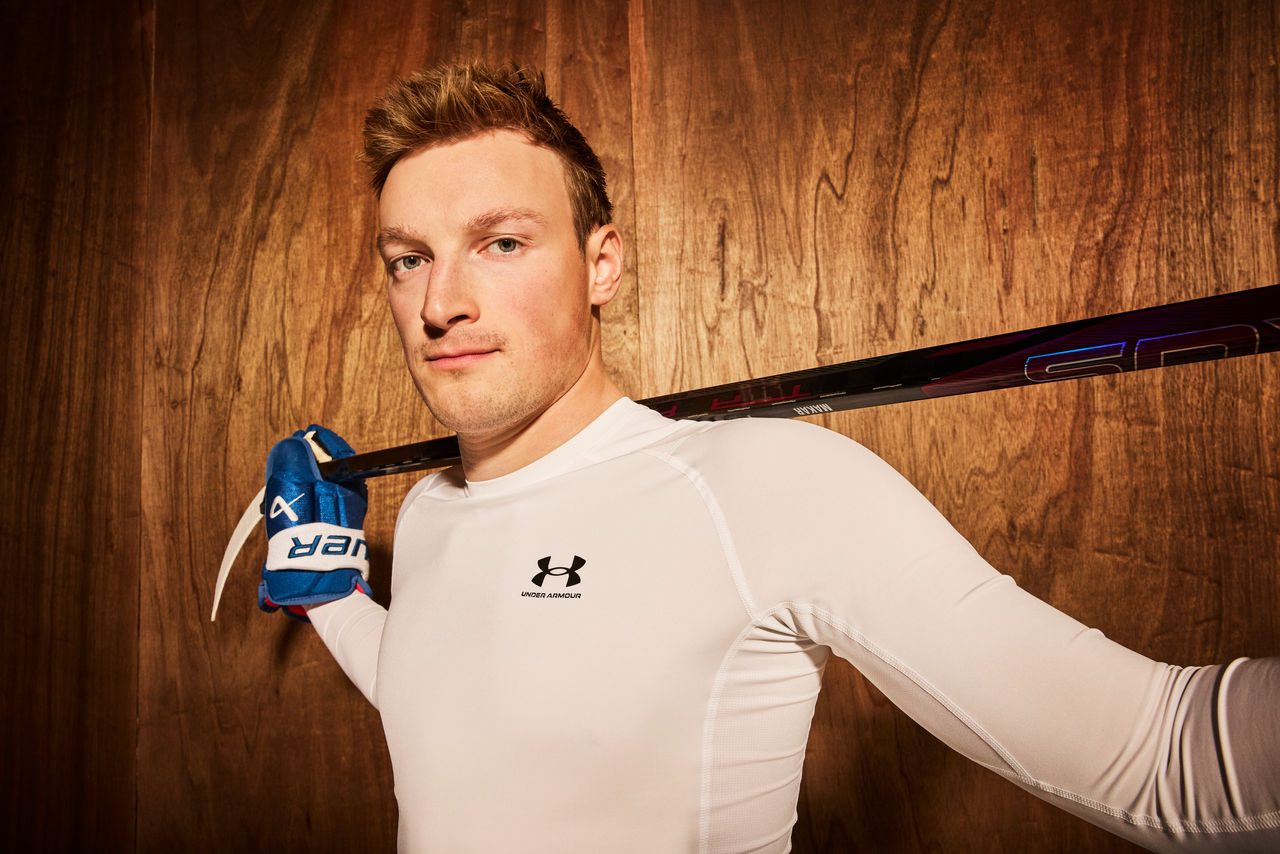

Under Armour Signs NHL Defender Cale Makar

Under Armour is thrilled to welcome this extraordinary talent to its roster of athletes. A Calder, Norris, and Conn Smythe Trophy winner, all before the age of 25, Colorado Avalanche defenceman Cale Makar is a generational hockey talent and one of the best in the NHL.

Sharon Lokedi Secures Monumental Third Podium at the New York City Marathon

Crossing the finish line in 2:20:07, Lokedi battled through a world-class field to claim a top three spot and eclipse the race’s previous course record, adding another milestone to a year already defined by excellence.

Freddie Freeman Wins Back-to-Back World Series Titles

Under Armour athlete and Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman Freddie Freeman helped the Dodgers clinch the 2025 World Series title, defeating the Toronto Blue Jays in a showstopping seven-game series. With this victory, Freeman earns his third World Series ring, further cementing his status as one of the fiercest competitors in the game.

Under Armour Launches Lab96 Studios

Under Armour introduces Lab96 Studios, its new in-house content studio designed to deliver athlete stories in fresh, episodic, and cinematic ways.

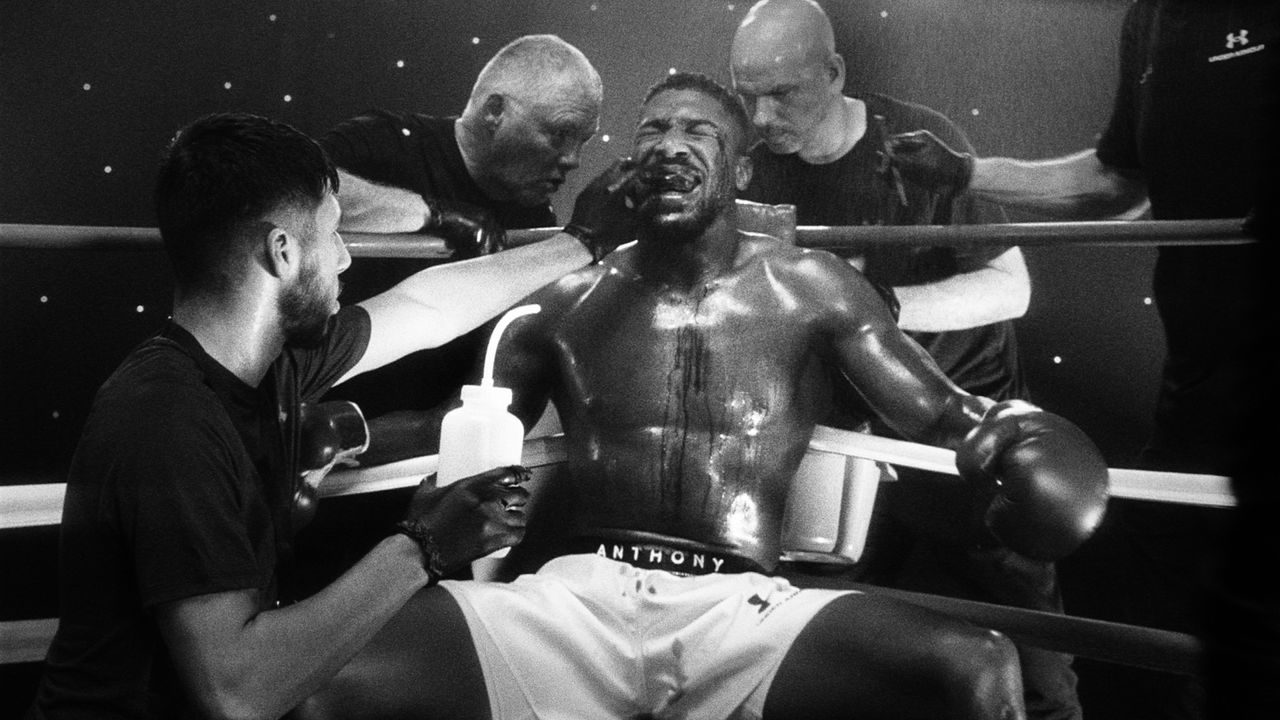

Fight Worlds Collide as Under Armour Unites Anthony Joshua and Paddy ‘The Baddy’ Pimblett in Combat Crossover

In a meeting of calm and chaos, two-time heavyweight boxing world champion Anthony Joshua and UFC lightweight contender Paddy ‘The Baddy’ Pimblett came together with their performance partner Under Armour.

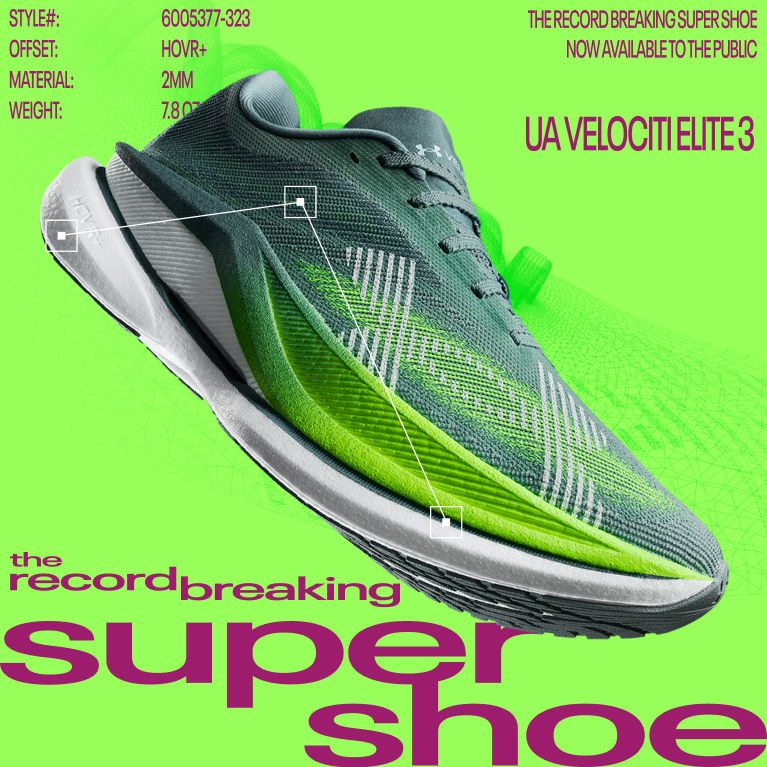

Under Armour’s Next Generation of Velociti is Engineered for Speed and Proven on the Podium

Under Armour has introduced the next evolution of its flagship technical running platform: the Velociti Elite 3, Velociti Pro 2, and Velociti SPD. Engineered for speed, precision, and elite-level performance, Velociti is built for athletes who demand measurable results on the track, road, or treadmill.

Under Armour and JUJUTSU KAISEN Unleash Limited-Edition HeatGear® Compression Shirt Capsule

Under Armour is proud to unveil a bold new collaboration with JUJUTSU KAISEN, the globally acclaimed anime series streamed by Crunchyroll, the global anime brand fueling fandom worldwide.

Under Armour to Become Official Apparel Provider of Georgia Tech Athletics in 2026

In 1996, Georgia Tech became Under Armour’s first college customer with the purchase of HeatGear and ColdGear. The two are officially teaming up again, Under Armour will be the official provider of uniforms, apparel, footwear, and accessories for the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets beginning July 1, 2026.

Under Armour and UNLESS Introduce Three Regenerative Footwear Styles

Under Armour and UNLESS launch three new lifestyle sneakers that embody UNLESS’s regenerative ethos, inspired by nature’s circular systems, with a goal of creating not just the best sneakers in the world, but the best sneakers for the world.

Under Armour’s Celebrates 21st Annual ‘Armour Day’ with Community Service Across the City Of Baltimore

Under Armour employees come together for the purpose of community service to positively impact the brand’s hometown of Baltimore.

UA Next All-America Game Announces 2025 Rosters; GameChanger Named Official Live Streaming, Highlights, Scorekeeping and Stats Partner

Baseball Factory and Under Armour announce the final rosters for the 2025 UA Next All-America Game, set for Saturday, Sept. 13, at Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore.

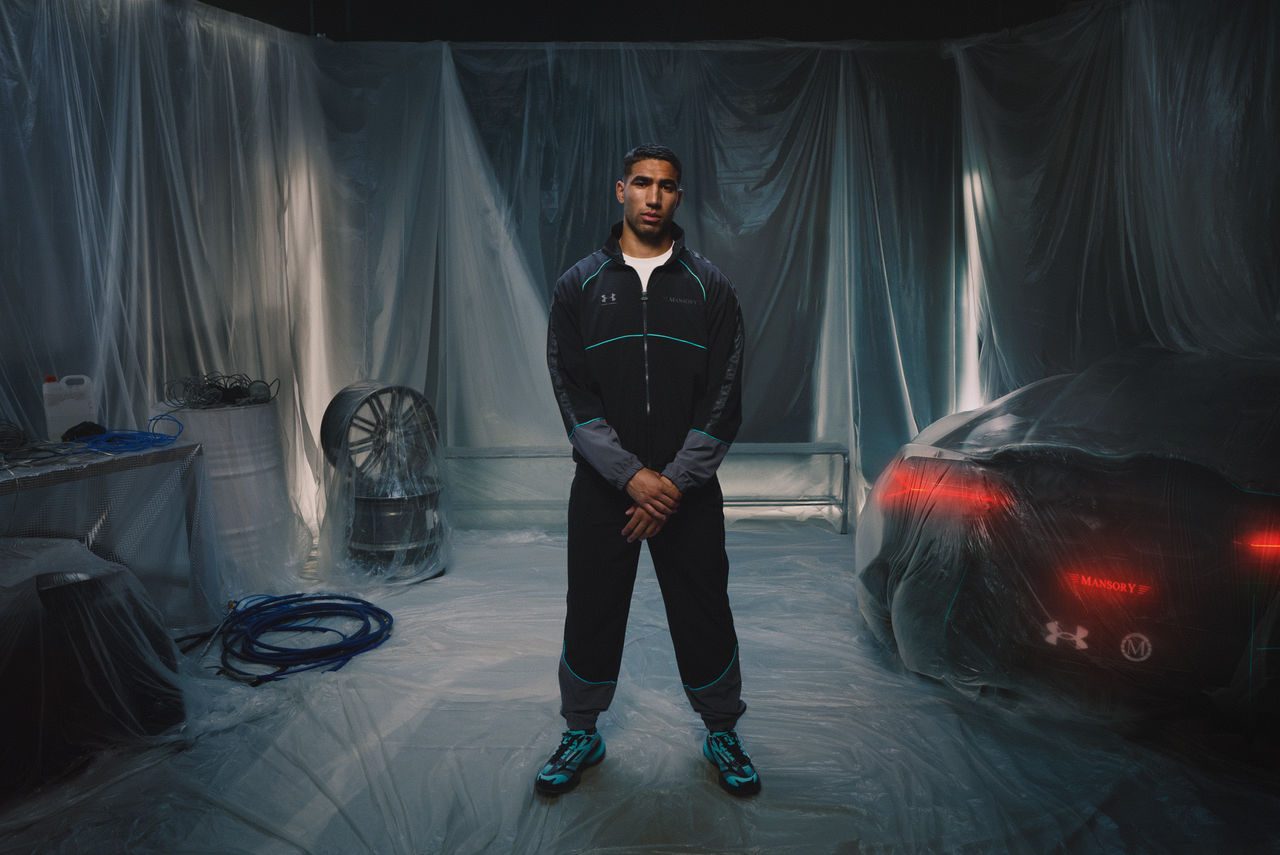

Under Armour X Mansory Collaboration Launches With a Face-Off Between Two Football Icons

Under Armour’s much anticipated collaboration with luxury automotive customizer Mansory will finally be launching at retail with a full collection.

Under Armour Launches “We Are Football,” a Global Salute to the Players and Communities Powering the Game

A landmark campaign that celebrates the athletes and energy defining the game today. Built to deepen its connection to football culture, We Are Football reframes Under Armour’s performance-driven DNA through a modern lens, speaking directly to the next generation shaping the future of the sport.

Curry Brand Unleashes the Fox 2

As one of the fastest players in the NBA, De’Aaron Fox needs a sneaker that can keep up with his quickness and the Fox 1 from Curry Brand delivered just that.

Under Armour launches ‘Be The Problem’ football campaign

Live in the UK, France, and Spain starting August 15, Under Armour’s Be The Problem campaign marks the brand’s latest offensive in football with a distinctive new voice. As the new season kicks off, the campaign delivers a bold call to arms for a new generation of athletes, flipping the notion of “the problem” on its head. Once a label used to erode confidence and diminish dreams, Under Armour reframes it as a competitive edge – defining how modern athletes think, prepare, perform, and dominate their sport.

Premier League Champion Ibrahima Konaté Joins Under Armour as the Brand’s Latest Football Signing

A commanding starter in Liverpool’s championship-winning backline and vice-captain of the French national team, Konaté is renowned for his strength, composure, and elite mentality on the world’s biggest stages. His relentless pursuit of excellence aligns seamlessly with Under Armour’s unwavering commitment to performance and innovation.

Tini Stoessel Joins Under Armour, Championing a New Era of Performance and Self-Expression

Under Armour has announced a dynamic new partnership with Argentinian pop sensation Tini Stoessel, marking a bold step in the brand’s mission to redefine what it means to be an athlete today. Known for her powerhouse performances and global influence, Tini joins Under Armour as its newest brand ambassador, bringing her signature blend of strength, authenticity, and style to the forefront of sport and culture.

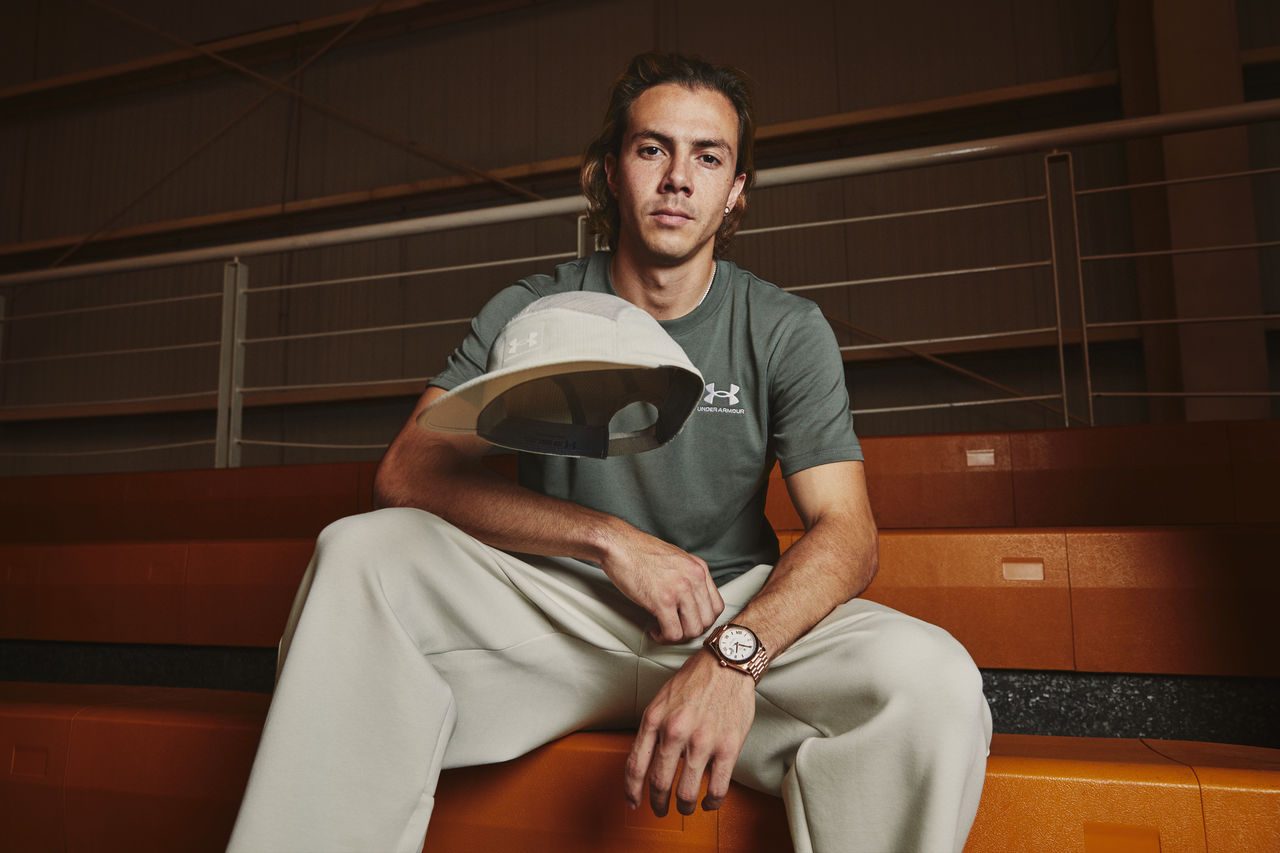

Christo Lamprecht Claims First Professional Victory at Pinnacle Bank Championship

Christo Lamprecht’s rise in professional golf has hit a major milestone. With a dramatic birdie from the greenside bunker on the 18th hole at Indian Creek Golf Club, the 24-year-old South African clinched his first professional victory and Korn Ferry Tour title at the Pinnacle Bank Championship, finishing at 19-under 265.

Introducing The Series 7: The Future of Basketball Performance Footwear

The first of its kind “super shoe” from Curry Brand brings next-level performance to the hardwood—designed for speed, control, and endurance

Mikel Arteta joins Under Armour as a Global Ambassador

One of the game’s top managers is set to bring his unique leadership and world-class knowledge as Global Ambassador at Under Armour.

Under Armour Launches UA HALO

Built for the everyday athlete, UA HALO introduces a holistic approach to performance, where symmetry, balance, and harmony are both aesthetic choices and functional principles.

Asian University Basketball League (AUBL) Announces Under Armour as Its Official Performance Outfitter and Game Ball Partner

The Asian University Basketball League (the AUBL) has announced a landmark partnership with Under Armour as the league’s official performance outfitter and game ball partner. Select players from the AUBL will travel to Chongqing this summer to meet with 4-Time NBA Champion Stephen Curry and participate in an exhibition game hosted by Curry Brand and Under Armour.

Under Armour Launches UA SOLA

Under Armour introduces UA SOLA, it blends sport heritage with street-smart style, delivering comfort and confidence wherever the day leads.

Under Armour Welcomes Coach RAC as Newest Brand Ambassador

Under Armour is proud to welcome RobertAnthony Cruz – better known as Coach RAC – to its growing roster of athletes redefining the future of sport.

Under Armour & Curry Brand Announce Curry Brand World Tour

Under Armour and Curry Brand today announce their marquee basketball initiative of the summer - the 2025 Curry Brand World Tour. Curry Brand—Stephen Curry’s basketball footwear and apparel line under Under Armour—is going global, returning to Asia for multiple stops and hosting Curry Camp in both the U.S. and China.

Toni Rüdiger Teases Under Armour X Mansory Collaboration in Football with Iconic Magnetico Elite 5 Boots at Fifa Club World Cup

UA athlete and Real Madrid’s centre-back Toni Rüdiger debuted Under Armour’s collaboration with luxury automotive customizer Mansory in football, with brand new Magnetico Elite 5 Mansory boots.

Under Armour Partners with the Chinese Rugby Football Association to Support Rugby and Flag Football Development in China

Under Armour today announced a significant long-term partnership with the Chinese Rugby Football Association (CRFA), making the global performance brand the official outfitter of the Chinese National Flag Football Team and the Chinese National Men’s 7s Rugby Team. This collaboration marks a strategic investment in the burgeoning rugby and flag football landscape in China, particularly as flag football prepares for its debut as an official sport at the 2028 Los Angeles Olympic Games.

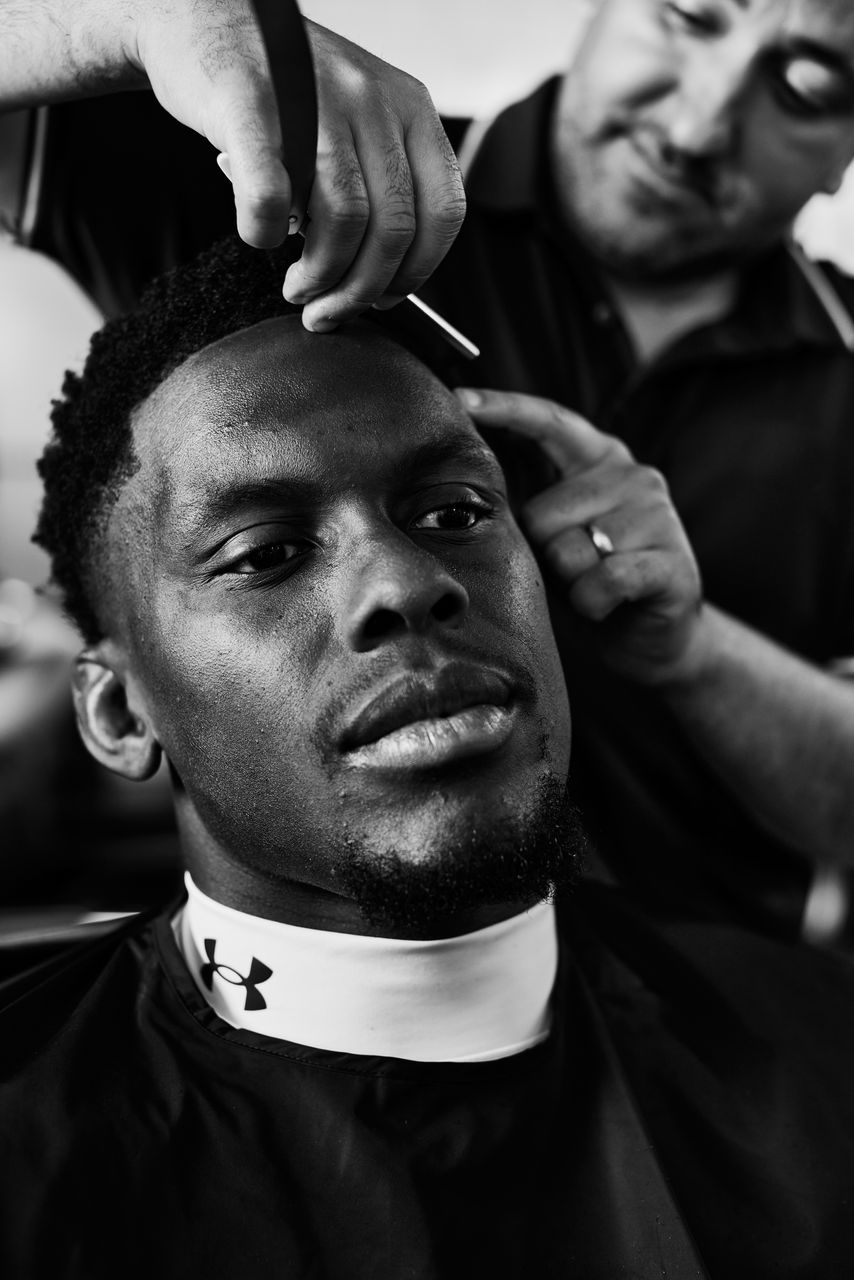

Maro Itoje Heads to the Barber as He Prepares to Captain the British & Irish Lions

Having already been named Saracens and England captain in the last 12 months, Maro has once again proven himself as one of the best in the game by being handed captaincy of the British & Irish Lions. It caps off a hugely successful year for Maro who has firmly established himself as a generational rugby talent.

Where Goals Begin: Jayde Riviere Hosts the Next Generation

Manchester United defender and Canadian Olympic Gold medalist Jayde Riviere returned home to give back in a big way—teaming up with Under Armour for the second consecutive year to host an immersive training experience for more than 30 youth players from Pickering Football Club (PFC), her hometown team.

Justin Jefferson and Under Armour Team Up and Take Off at Inaugural Flight School

Born out of a shared commitment to developing the next generation of athletes and providing them with resources needed to level up, Under Armour and Justin Jefferson recently hosted the inaugural Flight School, powered by UA NEXT. Held at IMG Academy in Bradenton, FL, this three-day camp set out to help grassroots football players navigate their journey from high school to collegiate football.

Curry Brand Adds Chinese Basketball Player Jacob Zhu

Today Curry Brand is excited to announce it has inked an NIL partnership with rising Chinese basketball star Jacob Zhu, known as Zhu Zheng in China. Zhu becomes the first athlete from China to sign with the brand and its second international athlete.

Duo of Next-Gen Footballers Join Under Armour Roster

Under Armour reinforces its commitment to the next generation of football talent with the signing of gifted English duo Lewis Miley and Sam Amo-Ameyaw.

Under Armour Underscores Commitment to Team Sports with Strategic Uniform Licensees

Under Armour announced the expansion of its longtime wholesale partnership with BSN SPORTS, a leading distributor of team sports apparel and equipment in the U.S., to include licensing for UA team sports uniforms. Beginning in January 2026, BSN SPORTS will become an official manufacturer of UA-sublimated uniforms, serving current and future organizations who partner with both BSN SPORTS and UA.

World Game’s Gold Medalist Diana Flores and Under Armour Strengthen Flag Football in Mexico

Under Armour and Diana Flores made history once again with the return of the UA Next Camp, an exclusive event designed to empower young female athletes in Mexico and develop their talent both on and off the field. The camp brought together more than 130 young flag football prospects, ages 15 to 19, for an intensive training program.

Comerse Al Rival

Ahead of El Clásico, Under Armour’s roster of top talent at FC Barcelona; Ferran Torres, Fermín López and Marc Casadó, have sent a playful message to their arch-rivals showcasing their ruthless hunger for success.

Introducing the No Weigh Backpack

For years, athletes have carried the same burden – and we are not talking about expectations or pressure. We are talking about their bags.

Where Dawgs Are Made: Kelsey Plum Hosts Third Annual Dawg Class

Under Armour and 2x WNBA Champion Kelsey Plum wrapped another electric edition of Dawg Class, a three-day elite training and mentorship experience for the best female collegiate basketball guards, held April 18–20 in Phoenix.

Sharon Lokedi Returns to The Boston Podium

On one of the most demanding courses in competitive distance running, Sharon Lokedi didn’t just show up—she delivered. The Under Armour athlete secured a first-place finish at the 2025 Boston Marathon with a time of 2:17:22, a new course record, further cementing her place among the sport’s most consistent and compelling competitors.

Under Armour Signs Next Wave of Football Elite Ahead of 2025 NFL Draft

Under Armour proudly announces the next era of elite football talent as the brand doubles down on its commitment to shaping the future of the game. Cam Ward, Luther Burden III, Nick Emmanwori, Matthew Golden and Tyler Booker are the latest additions to the UA Football roster – each one poised to make an impact in the 2025 NFL Draft and beyond.

Under Armour Empowers Women with New Courtside Collection – Born from Sport and Twisted for Culture

Sport isn’t just about competition—it’s a way of life. It fuels confidence, inspires independence, and shapes identity. With that ethos at its core, Under Armour is revolutionizing womenswear with the launch of the Women’s Courtside Collection, available starting today.

Under Armour and Unless Debut Regenerative Sportswear Collection at Milan Design Week

Under Armour and UNLESS spearhead a transformative shift in the sportswear industry by unveiling an innovative regenerative sportswear collection at Milan Design Week.

Under Armour Enters a New Era with UA ECHO

Under Armour is known for its relentless pursuit of performance innovation, creating gear that helps athletes push limits and break barriers. Today, the brand is stepping beyond the arena and into culture, making a bold statement with the launch of UA ECHO—a shoe that redefines what Under Armour stands for.

Under Armour signs world-class right-back Achraf Hakimi

Under Armour continues to make waves in football with the signing of Paris Saint-Germain and Morocco National Team star right-back, Achraf Hakimi, who joins the brand’s expanding list of incredibly talented young football athletes across EMEA.

Under Armour Powers Into the 2025 Majors Season with Elite Talent and Game-Changing Innovation

As the golf world eagerly anticipates the start of the 2025 majors season, Under Armour is once again stepping onto the fairway as the performance brand for the modern golfer. With a legacy of supporting elite athletes and a passion for pushing the boundaries of innovation, Under Armour is redefining golf apparel and footwear to give players every possible advantage.

Deep Range, Big Dreams: Eli Ellis Joins the Under Armour Family

Under Armour is proud to officially welcome Eli Ellis, a sharpshooting standout with unlimited range and a relentless work ethic, to its roster of elite basketball athletes.

National Football League Announces Under Armour as an Official Footwear and Glove Partner

Under Armour and the National Football League today announced a long-term partnership, under which Under Armour will become an official footwear and glove partner of the NFL. This agreement affirms both brands' commitments to innovation in athletic performance, fan engagement and youth development.

Under Armour Unveils the GLDN CHLD

Get ready to shine on and off the field. Under Armour has unveiled its latest innovation in football footwear: the GLDN CHLD cleats. Designed for players who dominate the game and embody confidence, these cleats are a bold fusion of cutting-edge performance and style, inspired by the opulence of jewelry and street culture.

Under Armour and Northwestern University Announce Extension of Partnership

Under Armour and Northwestern University today announced the extension of their partnership. Under Armour has been the official outfitter of Northwestern’s 19 varsity intercollegiate athletic programs since 2012.

Under Armour Debuts “Let Them Talk” Campaign in partnership with RDCWorld

Under Armour and video creator collective RDCWorld have teamed up to launch an exciting new video content series titled, “Let Them Talk,” debuting just in time for college basketball’s biggest tournament.

Significant Disparities in Sports Engagement Found Among Washington D.C. Youth

More youth in Washington D.C. play organized sports than do so nationally, but the nation’s capital faces significant participation gaps in the most impoverished neighborhoods and among Black youth and girls, according to a report released by the Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative.

Under Armour Announces NIL Collegiate Class of 2025 to Celebrate the Postseason

Under Armour is thrilled to announce its NIL Collegiate Class of 2025, six of the top collegiate basketball players, three men and three women, who will help the brand celebrate the postseason in style.

Under Armour Welcomes Kieron Van Wyk to Golf Roster

Under Armour proudly welcomes Kieron van Wyk to its elite roster of golf athletes, reinforcing the brand’s commitment to equipping rising stars with cutting-edge performance gear. At just 23 years old, van Wyk has already made history, combining exceptional talent with an unshakable work ethic. As he prepares to take the next step in his career, Under Armour stands beside him, providing the innovation and support needed to fuel his success on golf’s biggest stages.

Under Armour Signs Nika Mühl

If there’s one thing you need to know about Croatian basketball player Nika Mühl, it’s that she knows how to make a statement. Whether through her bold fashion choices in the tunnel or with her exceptional playmaking on the court, Nika always makes her presence known, exuding an easy confidence and fierce competitiveness that has made her a favorite among basketball fans everywhere.

Under Armour and Curry Brand Celebrate a Good Weekend in the Bay

Under Armour and Curry Brand came together to celebrate 11-time NBA All-Star and now 2-time All-Star MVP Stephen Curry during basketball’s biggest weekend in San Francisco. With the festivities in Curry’s backyard this year, the brands showed up big time in the Bay with multiple activations, collaborations and unique product releases to show love for his legacy and remind basketball fans everywhere of their love for the game.

Curry Brand Makes Good on Community Impact Commitments

This past weekend, Curry Brand celebrated its 20th court refurbishment at McClymonds High School in Oakland, CA, fulfilling its commitment to renovate 20 safe places to play by 2025. With this final court completion, Curry Brand has officially made good on all of its community impact goals set in December 2020, renovating 20 courts, training 15,000 coaches and supporting 125 programs to ultimately impact 300,000 kids around the world.

Justin Jefferson Gives Back to His Community in New Orleans Ahead of Super Bowl LIX

Minnesota Vikings wide receiver and Under Armour athlete Justin Jefferson returned to his alma mater, Destrehan High School, on Thursday, February 6, to host a community event designed to inspire and empower the next generation of athletes.

Under Armour Adds Rasmus Neergaard-Petersen to Golf Roster for 2025 Season

Under Armour is proud to announce the signing of Denmark’s Rasmus Neergaard-Petersen, one of the DP World Tour’s brightest emerging talents, who will wear the brand’s performance apparel and footwear on and off the golf course in 2025.

Curry Brand Welcomes Davion Mitchell to Its Athlete Roster

Relentless. That’s the word that comes to mind when watching NBA point guard Davion Mitchell on the basketball court. His athleticism, his speed, his defensive mentality, his competitiveness and desire to be the best, all point back to that word.

Under Armour and BlacktipH Announce New Partnership

Under Armour today announced a multiyear partnership with BlacktipH, the world’s leading fishing show in subscribers and viewers, and a powerhouse in outdoor content development.

Under Armour Launches Shadow 3

Under Armour has once again raised the bar in athletic performance with the debut of the UA Shadow 3 soccer cleat. Designed for players who push boundaries with every sprint, cut, and strike, the UA Shadow 3 redefines what it means to dominate the field.

Under Armour Launches Infinite Elite 2 In Dubai

To mark the launch of the second iteration of Under Armour’s award-winning Infinite Elite franchise, UA hosted over 50 running guests from 9 EMEA markets in the growing health and fitness hub of Dubai in the UAE.

Under Armour Unveils First-Ever UA Next All-America Collaboration with Joshua Vides

Under Armour is set to host its 17th annual UA Next All-America Game Week in Orlando, Florida, gathering 24 of the top high school volleyball players and over 170 of the nation’s best high school and middle school football players for the event, which will take place on January 1st and 2nd, 2025, and will be broadcast on ESPN. This year, Under Armour will celebrate the occasion by introducing the first-ever UA Next All-America collaboration, designed in partnership with Southern California-based artist Joshua Vides. Under Armour is set to host its 17th annual UA Next All-America Game Week in Orlando, Florida, gathering 24 of the top high school volleyball players and over 170 of the nation’s best high school and middle school football players for the event, which will take place on January 1st and 2nd, 2025, and will be broadcast on ESPN. This year, Under Armour will celebrate the occasion by introducing the first-ever UA Next All-America collaboration, designed in partnership with Southern California-based artist Joshua Vides.

Barcelona FC striker Ferran Torres Joins Under Armour’s Impressive Roster of European Football Talent

Ferran Torres becomes the latest addition to Under Armour’s expanding list of incredibly talented young football athletes across their key markets of Spain and the UK.

Under Armour Strikes Partnership with Football Star Douglas Costa

Leading global athletic performance brand and Sport House, Under Armour is proud to announce its newest global Under Armour athlete, Douglas Costa, a renowned Brazilian footballer celebrated for his explosive speed, agility and creativity. Costa has signed a two-year endorsement deal with Under Armour, aligning with his marquee contract with Sydney FC in the A-League.

Rising Hip-Hop Star Lay Bankz Joins Team Under Armour

Under Armour is making bold moves into the cultural space with its latest partnership, signing hip-hop sensation Lay Bankz. Known for her electrifying stage presence, fearless fashion, and genre-defying sound, Lay embodies the type of artist Under Armour represents confident, versatile, and relentlessly authentic.

Under Armour and the Naval Academy Athletic Association Extend Partnership in a Multiyear Agreement

The Naval Academy Athletic Association and Under Armour announced December 11, 2024 the extension of their partnership in a multiyear agreement. The Naval Academy Athletics Association has one of the largest athletic programs in the country with 36 varsity intercollegiate teams. Their commitment to developing Midshipmen morally, mentally, and physically, perfectly aligns with Under Armour’s grit and determination to make athletes better.

Unrivaled Announces Under Armour as Its Official Uniform Partner and Performance Outfitter

Unrivaled, the groundbreaking professional women’s basketball league, announced today a multiyear partnership with Under Armour as its official and exclusive uniform partner and performance outfitter.

Under Armour Celebrates Grand Opening of New Flagship Store with Kelsey Plum and Nearly 200 Baltimore Student Athletes

The new 24,000 square-foot store is situated on the campus of the brand’s new Global Headquarters, bringing UA’s retail presence physically closer to its athletes, product, and innovation teams – the homebase where UA teammates work to shape the future of sports, push boundaries, and inspire the next generation of athletes.

Curry Brand Introduces Speed that Scares with the Fox 1

The need for speed is real in the game of basketball and no one plays with pace like Curry Brand athlete De’Aaron Fox. With speed that scares and a game that dazzles and defies boundaries, it was only right that Curry Brand create a sneaker that embodies the distinct play and personality of one of the NBA’s most impressive guards to date.

Empowering the Next Generation

Back for its third year, Jordan Thompson’s hands-on training camp returned for youth volleyball players in Houston, Texas. One of the many ways Jordan gives back to the game she loves, this camp provides mentoring for elite youth volleyball athletes, empowering them on their journey to compete.

Sacha Boey Joins Under Armour Football Roster and Embraces the Cold in Paris

Under Armour highlighted its commitment to developing young football athletes and its growing influence in Paris by hosting a display of defensive talent with Bayern Munich right-back Sacha Boey, the brand’s newest athlete, returning to the city that shaped his playing style.

Under Armour’s Project Rock Partners With Shepherd’s Men To Support Veterans

Many veterans return home with invisible injuries that aren’t easily understood or treated. But the SHARE Military Initiative—a comprehensive rehabilitation program for veterans with traumatic brain injuries and mental health concerns—is changing the way these wounded warriors are treated and giving them renewed hope.

Celebrating the Wins for Freddie Freeman

On Wednesday, October 30, 2024, Under Armour Athlete and Los Angeles Dodger’s first baseman Freddie Freeman won his second World Series and was named the 2024 World Series MVP.

Under Armour and DTLR Unveil School Spirit Rivalry Packs to Celebrate Historic Baltimore Football Tradition

In honor of the historic and iconic local rivalry between Baltimore City College and Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, Under Armour has partnered with lifestyle retailer and Baltimore community champion DTLR to co-create new school spirit Rivalry Packs. Dating back to 1889, the City vs. Poly rivalry is one of the oldest high school football rivalries in the United States, and one of Baltimore’s most highly anticipated sporting events of the year.

The Curry 12 Goes Global with ‘Gravity’

Following several limited releases, Curry Brand will officially launch the Curry 12 globally on Friday, October 18, in the ‘Gravity’ colorway.

Under Armour Lands In London For The Launch Of Its Unstoppable Sportswear Range

Under Armour continues to innovate with product solutions for the 24/7 athlete needs, this time with its latest sportswear collection, UNSTOPPABLE. Again demonstrating how Under Armour makes athletes better, both on and off the field.

Under Armour’s 20th Annual ‘Armour Day’

On Thursday, September 19, 2024, Under Armour marked its 20th annual Armour Day event with volunteer activations designed to positively impact and celebrate the brand’s hometown of Baltimore.

Under Armour and Jackson State University Extend Partnership Through 2029

Under Armour has renewed its contract with Jackson State University as the official outfitter of all 17 of its varsity sports through 2029.

Under Armour Unveils Special Breakthru 5 Sneakers in “Plum” Colorway

Today, Under Armour released a special limited-edition Breakthru 5 “Plum” colorway to celebrate Under Armour basketball athlete Kelsey Plum ahead of her 30th birthday on August 24.

Introducing the ARMR 037 Uniform

Introducing the ARMR 037 uniform, the brand’s most innovative American football design to date.

The Future Just Got Better – The Curry 12 Has Arrived

The Curry 12 has arrived – ready to propel Stephen to peak performance in the next chapter of his career and help hoopers all over the world do their thing.

Elite 24 Showcases the World’s Next Generation of Basketball Stars

On August 10, Under Armour returned to New York for the first time since 2016 to host its UA Next Elite 24 event in Brooklyn, bringing together 48 of the world’s most elite high school basketball players for an unforgettable competition.

Under Armour Announces Eric Liedtke as Executive Vice President of Brand Strategy

Under Armour, Inc. today announced that Eric Liedtke will join the company as Executive Vice President of Brand Strategy following the completion of its acquisition of UNLESS COLLECTIVE, INC (UNLESS), a zero-plastic regenerative fashion brand.

Rising Golf Star Christo Lamprecht Joins The Under Armour Family

The world of golf is buzzing about Christo Lamprecht. The 23-year-old golfer from South Africa is one of the most promising rising stars in the game. At just 16-years old, Lamprecht won the South African Amateur Championship—the youngest player in history to win it. At Georgia Tech, Lamprecht was All-American three times, 2024 Atlantic Coast Conference Player of the Year, the winner of three collegiate titles, and ended his senior year as the top ranked amateur player in the world. Now, Christo Lamprecht has decided to turn professional—and join Under Amour’s golf roster.

Under Armour Introduces UA Unstoppable

Under Armour has embarked on a new era of sportswear with its evolved collection, Unstoppable, for FW24 and beyond, announcing its commitment to building a sportswear offering that supports athletes off the pitch. Using premium performance materials and featuring fresh and stylish silhouettes, UA Unstoppable is designed to meet the 24/7 performance needs and style expectations of the modern athlete.

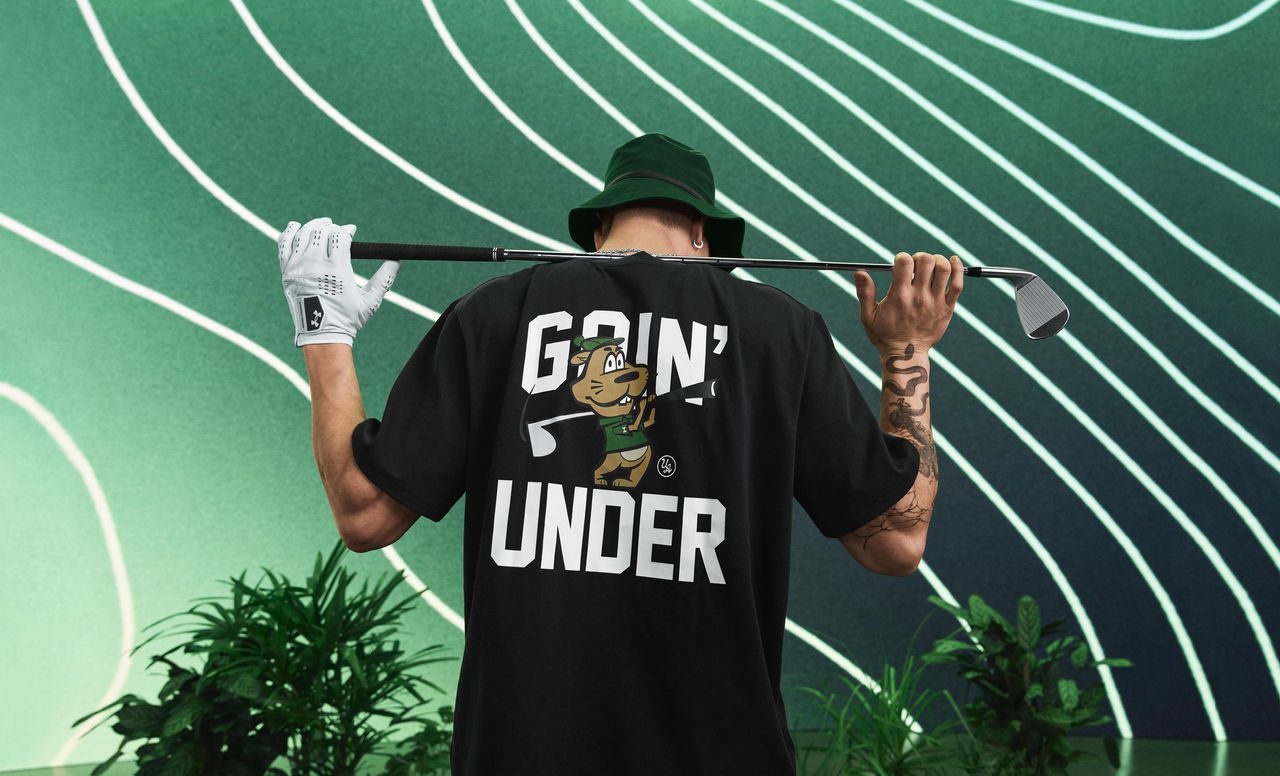

Gear Up To Go Low With Under Armour's Latest Golf Collection

This summer, Under Armour is putting a modern twist on the golf classics with the release of the UA Goin’ Under Golf Collection. The Goin’ Under Collection offers head-to-toe pieces for both men and women that golfers can wear from the course to the clubhouse. In this collection, golfers will hit the green feeling optimistic and inspired to lower their score – because when you look the part, you play the part. Why not make today the day that you ‘go under’ par and play the round of your life?

Under Armour and Diana Flores Make History with Groundbreaking Flag Football Camp in Mexico

Under Armour and UA Next have reached a significant milestone in youth sports in Mexico by hosting a special flag football clinic exclusively designed for young female athletes eager to pursue their athletic dreams.

Under Armour Basketball Celebrates Female Representation at the 2024 WNBA All-Star Weekend in Phoenix

This year at the WNBA All-Star, Under Armour made sure a group of local middle school girls got to see their potential, providing a special experience focused on female empowerment and representation alongside some of Under Armour’s most notable WNBA athletes.

Under Armour Hosting Free Event for Baltimore City Student Athletes on August 3

On Saturday, August 3, Under Armour and Project Rampart are hosting a community event at UA’s Tide Point campus to help you get ready for the fall 2024 athletic season.

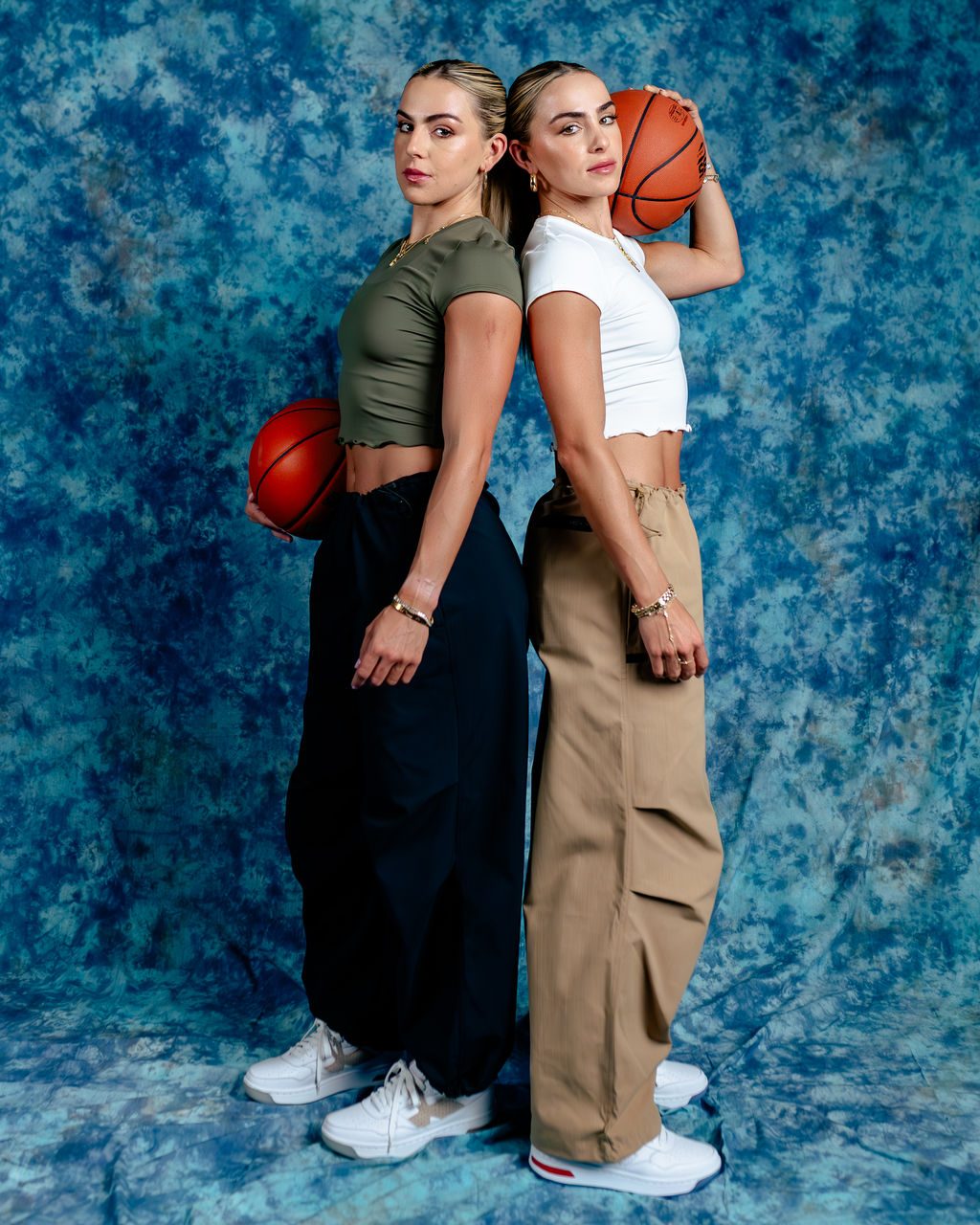

Under Armour Welcomes its Newest Brand Ambassadors: Haley and Hanna Cavinder

Under Armour announced today that it has signed University of Miami Point Guard Haley Cavinder and Guard Hanna Cavinder to a multi-year partnership, marking the first exclusive apparel and footwear deal for the twins.

Under Armour Returns to the Warrior Games for Seventh Year to Honor Military Community

Under Armour’s support for the military community knows no limits. For years, the brand has remained committed to positively impacting active-duty service members, veterans, and their families. One of the ways this comes to life is through Under Armour’s continued support of the annual Department of Defense Warrior Games.

Kick It with Jayde Riviere

Jayde Riviere, Manchester United and Canadian national team player, and Under Armour athlete, gave back to her home Pickering Football Club (PFC) by hosting an immersive training experience for 32 youth players.

University of Maryland and Under Armour Announce 12-Year Extension of Iconic Partnership

After two decades of partnership, the University of Maryland has renewed its partnership with Under Armour, extending its agreement for an additional 12 years through 2036.

Keisei Tominaga Signs with Curry Brand

Keisei Tominaga made quite a splash as a breakout star on the NCAA basketball scene this past season.

USA Football and Under Armour Form Multi-Year Partnership to Support U.S. National Teams and Grow the Game of Football

USA Football, the sport’s governing body in the United States and the organization responsible for creating and leading the U.S. National Teams, and Under Armour, the innovative performance brand, today announced a multi-year partnership through the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. The partnership aims to allow every athlete to participate, ultimately growing the game of football.

Sport for All

In celebration of Pride 2024, Under Armour is turning its attention to the playing field with a campaign spotlighting three inspiring voices of Division 1 athletes from the LGBTQ+ community.

The Future of Stretch

In 1996, Under Armour proved a single shirt can change the game forever. The brand’s original performance stretch, compression technology wicked away sweat faster than anything else out there and kept athletes cool, dry and light. Ever since, Under Armour has continued to change the game with innovative performance gear. Now, it honors its innovation heritage as it looks to the future of stretch.

An Ode to an Icon: Celebrating Kelley O'Hara

After 15 impressive years of playing professional soccer, Kelley O’Hara has announced her decision to retire.

Under Armour Signs English Amateur Golf Sensation Kris Kim

Surrey-based Kris Kim, who starred in Europe’s victory at last year’s junior Ryder Cup, will compete in Texas against some of the best players in the world, with the field at the CJ Cup Byron Nelson at TPC Craig Ranch also including former number one and fellow Under Armour athlete Jordan Spieth.

Under Armour Signs Tottenham Hotspur FC & Spain's Pedro Porro

Under Armour continues its commitment to growing its elite football roster by signing Tottenham Hotspur and Spain National Team player Pedro Porro. Porro joins an exciting roster of Under Armour top-tier players, including Antonio Rüdiger (Real Madrid), Malick Thiaw (AC Milan), Eddie Nketiah (Arsenal) and Fermin Lopez (FC Barcelona).

Under Armour Announces Yuron White as SVP, Sportswear, Run, Basketball/Curry & Collaborations

Under Armour is proud to announce that on April 29, 2024, Yuron White joined the company, bringing 25 years of experience working in sportswear, with deep expertise in footwear

Under Armour Keeps Young Athletes Cool in the Heat of Madrid

Under Armour HeatGear® Baselayer has been a staple in athletes' uniforms since its launch in 1996. To highlight the key performance features of the latest iteration, UA organised the 'Power Through Pressure' challenge in Madrid, Spain. Held at Madrid City Football Academy, the experience brought together football creators, media, performance specialists, and Under Armour athlete Antonio Rüdiger to showcase the benefits of UA's original performance baselayer.

Curry Brand's De'Aaron Fox Kicks Off New Campaign with UA Phantom 1

De’Aaron Fox is the face of a new campaign for Under Armour with partners Foot Inc., reintroducing the UA Phantom 1

(Dawg) Class is Back in Session

Under Armour and Kelsey Plum are coming together once again to host the second year of Dawg Class, powered by UA NEXT.

Maryland Tough, Baltimore Strong

In partnership with the Baltimore Community Foundation, Under Armour has released a specially designed shirt to raise awareness and support for the short and long term needs of its community following the March 26 Key Bridge tragedy.

Another Marathon, Another Podium

On Monday, April 15th, Under Armour Athlete Sharon Lokedi finished second in the Boston Marathon during her race debut with a run time of 2:22:45, just 0:00:08 behind first. In 2022, Lokedi became the fourth woman to win the New York City Marathon in her race debut and followed that with a third-place podium finish in 2023. Traditionally specializing in the 5K, 10K, and half marathon distances, the New York City Marathon was Lokedi’s first. Now, she’s podium finished her third marathon for a 3/3 streak using the same combination of all-star preparation and performance outfitting. This year, Lokedi wore the second iteration of Under Armour’s award-winning marathon racing shoe— the UA Velociti Elite 2—and trained under Stephen Haas and Pat Casey with UA Mission Run Dark Sky Distance.

Introducing The Hat Only Under Armour Could Make

Under Armour continues to push the boundaries of innovation as it develops products that athletes cannot live without. It’s already been a busy year for Under Armour but the performance brand isn’t stopping now—Under Armour is excited to introduce the UA StealthForm Hat, a foldable travel-friendly hat engineered to fit your head, breathe easy, and wick sweat all year round. The hat is anatomically molded with seamless construction for a custom fit—and, with its unstructured design, it’s washable and completely packable, snapping back into shape with no creases with ease. Smash it in a ball and it bounces right back. This is the hat only Under Armour could make.

MiLaysia Fulwiley Signs With Curry Brand

In November 2023, MiLaysia Fulwiley made a name for herself in the basketball world when a play of her taking the ball coast to coast for a basket in South Carolina’s season opener went viral.

Under Armour Announces Leadership Transition

Under Armour, Inc. (NYSE: UA, UAA) today announced that Kevin Plank will become President & Chief Executive Officer, effective April 1, 2024.

Forever Is Made Now

Under Armour has been providing AJ with leading performance solutions in and out of the ring since 2015, supporting him on his journey to become a two-time unified heavyweight world champion over the last eight years. Ahead of his ‘Knockout Chaos’ clash with heavyweight mixed martial artist and professional boxer Francis Ngannou, Under Armour marked the renewal of their long-term partnership with the release of an AI sports commercial with AJ, entitled ‘Forever Is Made Now’.

Under Armour Champions Women In Sports With Latest Collection

Under Armour stands for equality, both on and off the field and court, and has committed itself to celebrating, supporting, and championing female teammates and athletes. As an extension of that support, Under Armour, in partnership with WNBA superstars Kelsey Plum and Diamond Miller, is releasing a limited-edition product line that pays homage to female trailblazers everywhere in honor of Women’s History Month.

Curry Brand Completes 12th Court Revitalization in New York City

Curry Brand, powered by Under Armour, completed its twelfth court refurbishment at DREAM Charter School East Harlem in New York City as part of the brand’s mission to impact 100,000 youth and renovate 20 safe places to play by 2025.

Under Armour Leaves London Guessing With Holographic Unveiling Of Shadow Elite 2 Boots

Under Armour amazed the London football community with a state-of-the-art holographic presentation of its latest innovation—the Shadow Elite 2 Football Boot. At an exclusive event hosted at Village Underground, Shoreditch, UA brought together elite athletes, creators, and media for an immersive look at the future of football footwear.

Under Armour and Curry Brand are knocking down straight 3’s for this years 2024 NBA All-Star Weekend

Together the brands gear up for the 73rd Annual NBA All-Star with new, highly anticipated All-Star-inspired product and a “Curry’s Gameroom” pop-up activation dedicated to the fans

The Only Shoe With 2 Modes Just Got Better

Under Armour is re-introducing the most versatile training shoes we’ve ever made with a supersized midsole for mega energy. With its convertible heel and new pumped-up midsole, the UA SlipSpeed Mega flexes between slip and speed modes with style.

Under Armour Appoints Kevin Ross as Senior Vice President, Managing Director of EMEA

Under Armour today announced the appointment of Kevin Ross as its new Senior Vice President, Managing Director of Europe, Middle East & Africa. With nearly 20 years of experience growing high profile brands including adidas, TaylorMade, Under Armour, and Yeti, Ross brings proven talent and regional expertise to the company.

RISE TOGETHER: UNDER ARMOUR CHAMPIONS HBCUS ON AND OFF THE COURT

This February, in honor of Black History Month, Under Armour is releasing a product collection inspired by its athletes of color at the collegiate level. Designed around the legacy of African American quilting and inspired by HBCU athletes, the collection is aimed at amplifying Black voices and the brand’s ongoing commitment to empowering Black athletes year-round.

Under Armour Launches the Ultimate Endurance Collection for That Run-Forever Feel

As the brand’s newest running footwear franchise, the UA Infinite Collection is all about delivering key footwear models that support long run days as well as everyday miles. Designed as the ultimate endurance Collection, the experience is boundless, effortless and limitless on the run. From the super plush feel of UA Infinite Elite to the balanced spring and support of UA Infinite Pro, these shoes were built to help you go the distance with ease and efficiency. The overarching goal of the Infinite Elite and Infinite Pro is to make the last mile feel better than the first.

Setting A New Standard On The Green

Under Armour works closely with its golf athletes to create performance-enhancing products that meet the needs of golfers of all skill levels. Designed with direct feedback from these athletes, Under Armour is excited to announce the Phantom Footwear and Drive Pro Series, designed for golfers that are looking for that competitive edge to allow them to play like a pro, without being one.

The FUTR X ELITE sets its sights on the future of basketball

Under Armour is committed to pushing the boundaries of style and innovation to meet the needs of aspiring, recreational, and professional athletes. Now, the brand is expanding its influence with the release of FUTR X ELITE: the pinnacle footwear model within Under Armour’s basketball portfolio that will redefine the category.

Celanese and Under Armour Develop Innovative New NEOLAST™ Fiber for Use in Performance Stretch Fabrics

Celanese Corporation, a global specialty materials and chemical company, and Under Armour, Inc., a global leader and innovator in athletic apparel and footwear, have collaborated to develop a new fiber for performance stretch fabrics called NEOLAST™. The innovative material will offer the apparel industry a high-performing alternative to elastane – an elastic fiber that gives apparel stretch, commonly called spandex.

Under Armour Bolsters Leadership Team with Appointment of New Chief Product Officer and New President of Americas

Under Armour, Inc. announced two new leadership appointments: Yassine Saidi as Chief Product Officer and Kara Trent as President of the Americas. Saidi will join the company on Jan. 29, and Trent, currently serving as the managing director of the company’s EMEA region, will assume her new role in February. Both will report directly to President and CEO Stephanie Linnartz.

FC Barcelona Rising Star Fermín López Joins Under Armour's Growing Football Roster

Fermín López becomes the latest athlete to join Under Armour's rapidly expanding roster of young, up-and-coming elite football players. The Spanish midfielder joins the likes of Antonio Rüdiger (Real Madrid), Ansgar Knauff (Eintracht Frankfurt), Malick Thiaw (AC Milan), Eddie Nketiah (Arsenal), Lewis Hall (Newcastle) and Anna Patten (Aston Villa), all of whom were signed by Under Armour in recent months.

Under Armour’s Breakthrough Fiber-Shed Test Method Now Available For Industry

Following years of research in its innovation lab, earlier this year Under Armour announced a breakthrough fiber-shed test method to help address the invisible, but daunting sustainability threat microfibers and microplastics pose to society and the planet. Now, the brand has teamed up with James Heal, a leading precision testing solutions supplier, to bring its award-winning test method to life.

Curry Brand Honors Hollywood Icon Bruce Lee

Mexican Soccer Champion Sebastián Cordova Joins the Under Armour Athlete Roster

Under Armour welcomes Mexican soccer player and current La Liga MX champion Sebastian Cordova to its athlete roster. Córdova, who also plays for Mexico’s National Soccer Team, will be part of the brand’s soccer campaigns in both Mexico and the Hispanic markets in the United States.

Nothing Hits Like the Original: Under Armour HeatGear OG

The new HeatGear OG utilizes the fit and fabric of the 1996 apparel – it’s thicker, more compressive, and ultra-cooling. This iteration brings Under Armour’s learnings and the needs of a new generation of athletes to life within the iconic cut of the original HeatGear.

Under Armour Unveils Custom Navy Football Uniforms Ahead of 2023 Army-Navy Game

The Army–Navy football game, presented by USAA, an enduring and cherished tradition in American sports, is about to see its 124th match-up. This epic showdown not only symbolizes the fierce rivalry between two of the nation's most esteemed military academies but also serves as a poignant reminder of the camaraderie and shared commitment of these future leaders in uniform. Under Armour, renowned for its innovation in athletic apparel, will once again partner with the Navy football team to outfit the Midshipmen.

Under Armour Embraces the Cold for NFL Weekend in Frankfurt

For the second year that the NFL International series visited Germany, Under Armour celebrated the sporting moment in Frankfurt by demonstrating how the brand pioneered the Baselayer back in 1996 and how it has since developed that technical product into today’s ColdGear Baselayer.

Curry Brand + TUFF CROWD Join Forces

Stephen Curry is making waves within the apparel space. From his tunnel walk arrivals to his looks on the links, Stephen has long had an eye for fashion. On the heels of the release of his 11th signature shoe with Under Armour—the Curry 11—Stephen and Curry Brand are now gearing up for his latest fashion endeavor, a collaboration with luxury streetwear brand TUFF CROWD.

Under Armour and Richfresh Unveil Custom Suits for University of Notre Dame and University of South Carolina Paris Match Up

As the women’s basketball teams from two Under Armour-sponsored schools—The University of South Carolina and The University of Notre Dame—go head-to-head in the Oui Play Classic in Paris, France on November 6, there’s never been a better time to raise awareness and make a statement. Under Armour is partnering with luxury tailor and designer, Richfresh, to elevate these athletes’ off and on-the-court experience by outfitting them in suits fit for the pros.

Under Armour Doubles Military and First Responders Discount Ahead of Veterans Day Weekend

In recognition of Military Family Appreciation Month and the upcoming Veterans Day holiday, Under Armour is offering military and first responders up to 40% off their purchases. Between now and November 19, the brand has doubled its in-store military and first responder discount from 20% to 40% at all UA Brand Houses and online, and from 10% to 20% at all UA Factory Houses.

De’Aaron Fox Signs with Curry Brand

Together, De’Aaron, Stephen, and Curry Brand will partner to collaborate and expand Curry Brand’s reach across the basketball space and beyond. With a shared respect and a joint passion for making an impact on and off the court, the All-Stars will evolve their relationship from competitors to partners.

Stephen Curry Armours Up for the 2023-24 Basketball Season

When Stephen Curry requested more compression sleeves to support an injury, Under Armour answered the call in less than 24 hours.

Under Armour Basketball Athletes Become WNBA Champions

Scoring 70 points to take home the 2023 WNBA Championship for a second year in a row, UA Basketball Athletes Kelsey Plum and Cayla George led their team to victory with a three to one win in a five game series over New York. Wednesday night’s win cements Las Vegas’ status as the first team to win back-to-back titles since Los Angeles in 2001 and 2002.

Jarace Walker Joins the Under Armour Athlete Line-Up

Under Armour is thrilled to announce that Jarace Walker— professional basketball player and rookie standout, power forward for Indiana, and familiar face around Under Armour since his high school days—is an official UA athlete. Both Jarace Walker and Under Armour look forward to pulling from a collective experience to chart a new course for up-and-coming athletes.

Under Armour Appoints Gap Inc. Veteran, Shawn Curran as New Chief Supply Chain Officer

Today, Under Armour announced that following a comprehensive search and interview process, retail industry veteran Shawn Curran will join Under Armour as Chief Supply Chain Officer, reporting to President and CEO, Stephanie Linnartz.

The Future of Curry Starts Now

On Friday, October 13, Stephen, Curry Brand, and Under Armour will release the 11th iteration in his signature shoe portfolio, marking a monumental milestone that puts Stephen and Under Armour in an elite class of signature shoe lines alongside other basketball greats. Leveraging a futuristic design that celebrates the Future of Curry and his everlasting impact on basketball culture, the Curry 11 boasts a bold and disruptive flair, with the technology needed to fuel hoopers’ performance on the court.

Ripken Baseball Names Under Armour Exclusive Apparel Partner

Ripken Baseball®, the leader in sports experiences, announced they have entered a multi-year partnership with Under Armour® (NYSE: UA, UAA) to be the exclusive apparel company for Ripken Baseball’s six properties, hundreds of tournaments, and multisport events.

When In Doubt, Protect This House

Six months after Protect This House officially re-entered the global sports vernacular, Under Armour has teamed up with Minnesota superstar wide receiver, Justin Jefferson, and legendary record producer, London On Da Track, to record and release a new iteration of the iconic rallying cry to show the world what it really feels like to be an elite athlete in today’s game.

Under Armour Publishes FY2023 Sustainability & Impact Report

Under Armour, Inc. today published its FY2023 Sustainability & Impact Report, providing a progress update on 23 goals the company announced in 2022 as part of its work to reduce the environmental footprint of its products and operations while accelerating its social and community impact.

Under Armour Announces John Varvatos as Chief Design Officer

Today, Under Armour is proud to announce that fashion industry veteran John Varvatos will join the company as Chief Design Officer, effective September 11, 2023. Varvatos started consulting for UA earlier this year and brings his deep expertise in style and form to the company. Varvatos will lead the creative design direction of the company and oversee the design studios in New York, Baltimore and Portland, Oregon.

Eddie Nketiah Celebrates New Under Armour Partnership By Opening Latest Under Armour Brand House on Oxford Street

Baltimore Ravens & Under Armour Unveil Custom Uniforms for Inaugural Season of Girls' Flag Football with Frederick County Public Schools

The Baltimore Ravens and Under Armour joined forces to provide custom uniforms for female student-athletes as part of the inaugural season of girls’ flag football with Frederick County Public Schools (FCPS).

Under Armour Creates the Ultimate Team Talk Using the Power of AI

Top Boy star and football fan Ashley Walters brought the speech to life with his iconic voice, combining the powers of man and machine in an innovative and authentic manner.

Curry Camp Convenes Basketball's Best in the Bay Area

Over the weekend, Stephen Curry headed to the courts at Menlo Park to put on his annual elite hands-on training, giving youth hoopers the opportunity of a lifetime to learn from and play alongside the three-point king himself.

Under Armour and Notre Dame March On Together

It has been nearly a decade since Under Armour and Notre Dame joined forces in a partnership that epitomized the union of tradition and performance. With the vision to elevate and inspire student-athletes, UA and the Fighting Irish have renewed their partnership in an agreement that reflects their shared commitment to authenticity, innovation and achievement.

Diana Flores Joins Under Armour as the First Flag Football Global Ambassador

Under Armour welcomes Diana Flores, world flag football champion, as a new Global Ambassador addition to UA Athlete roster. Flores is the first flag football athlete to join the Under Armour family and, at 25 years old, is an inspiring example of the resilience and dedication it takes for young athletes to always strive for more.

A New Way to Score More

Beginning July 31, Under Armour’s U.S.-based consumers will have a new way to score more with the launch of Under Armour’s “UA Rewards” loyalty program. In Under Armour’s drive to Make Athletes Better, our most loyal consumers will be able to connect to the brand in new and rewarding ways.

Ready For Battle

The biggest stage in the world has arrived for female global football players. Every practice, training session, and qualifier has gotten them to this point with their hopes and hard work laid out for everyone to see. The Women’s World Cup not only showcases the best athletes around the globe but provides a well-earned chance for the world to celebrate their success.

Under Armour Basketball Is Coming to WNBA All-Star Weekend in Las Vegas

Under Armour, Kelsey Plum and Diamond Miller are ready to turn up the heat in Las Vegas for the upcoming WNBA All-Star Weekend. To celebrate the sport and encourage even more young athetes to get involved in women’s basketball, UA will host various opportunities for fans of all ages to engage with some of UA’s top women’s basketball stars and truly learn what it means to Protect This House.

Under Armour Announces Changes to Executive Leadership Team

Under Armour, Inc. (NYSE: UA, UAA) today announced a series of senior executive leadership team changes supporting the company's Protect This House 3 (PTH3) strategy.

Future 50 Cranks Up the Preseason Heat

Back for its 8th year, the elite football camp welcomed 50 of the best juniors and seniors in high school football to one of the most coveted events in the UA Next circuit.

Welcome to the SqUAd: Diamond Miller, Laeticia Amihere, and Marina Mabrey

As the confetti settles on a record-breaking women’s college basketball season and the WNBA season tip off gets underway, Under Armour is keeping the momentum of women’s basketball on fire both on and off the court.

Manchester United Defender and Canadian Gold Medalist Jayde Riviere Joins Under Armour Roster

At just 22-years-old, Jayde Riviere of Pickering, Ontario, Canada, already has a storied international career and she’s just getting started. She was part of the Canadian gold medal-winning squad at the 2020 Summer Olympics, has represented Canada at the FIFA World Cup, and most recently, has signed with Manchester United FC through to the 2024-25 season.

Anthony Joshua Gets Under Armour’s Search for London’s Future Athletes off to Smashing Start

Under Armour athlete Anthony Joshua unveiled the home for Under Armour (UA) Next, an athletic programme designed to identify, train, and develop London’s young athletes and sports leaders of tomorrow.

(DAWG) CLASS POWERED BY UA NEXT IS IN SESSION

Born out of her now famous ‘dawg mentality’ and a need for a smoother transition to pro basketball that Kelsey experienced firsthand, Under Armour and Kelsey Plum recently hosted the inaugural Dawg Class powered by UA NEXT. Held at IMG Academy, this three-day camp set out to help women college athletes navigate their journey from college basketball to the professional level. Inspired by Kelsey’s jersey #10, Kelsey engaged on and off the court with nine of the top women’s college basketball guards, providing them with the tools and insights to succeed as a first step to increasing equity in sports.

Antonio Rüdiger Joins Under Armour Roster

Rüdiger is now wearing the Under Armour Clone Magnetico Pro 2 boot, and the brand is committed to helping him be the best he can be on the football field week in, week out.

A Golf Season Unlike Any Other

Professionals like Jordan Spieth have come to rely on Under Armour for technologies and innovations that provide that extra edge on the greens. As the golf brand for athletes, Under Armour knows exactly what the seasoned pro and the beginner need to take their game to the next level – whether you’re playing at Augusta or on your local course.

Under Armour and Stephen Curry Lock In Groundbreaking Partnership

Under Armour and Stephen Curry became a team in 2013. What started as an underrated point guard only a few years into the league, and a challenger brand looking to shake up the sporting industry, has become an iconic partnership with disruption and innovation at its core. Now, the two have amplified their unique partnership even further, forging a long-term commitment to serve athletes and communities and drive mutual success for years to come.

Under Armour Calls On A New Generation To Protect This House

With the help of current and future basketball legends Stephen Curry, Kelsey Plum, Aliyah Boston, and Bryson Tucker, Under Armour is bringing back Protect This House.

Trent Alexander - Arnold Smashes Open New Under Armour Brand House in Liverpool

Under Armour has launched its first UK Brand House at Liverpool ONE in emphatic style. To mark the occasion, Under Armour athlete and dead ball specialist Trent Alexander-Arnold took on the challenge of taking a free-kick to smash open the windows and officially launch the new store.

Under Armour Announces New Methodology to Measure Fiber Shedding

Under Armour, Inc. today announced it has developed a new testing methodology to help fight fiber shedding at its source and support progress toward the company's sustainability goal for 75% of fabrics in its products to be made of low-shed materials by 2030. Under Armour's innovative test method offers a simplified process to accurately measure a fabric's propensity to shed.

Introducing Dawg Class with Kelsey Plum

To pave the way for young women and show them what a future in sports can look like, Under Armour and Kelsey Plum are launching the inaugural Dawg Class. Hosted at IMG Academy in April, this mentorship program will help women college athletes navigate the transition to the professional level.

Under Armour and City Schools Celebrate Project Rampart

Today, Under Armour and City Schools celebrated Project Rampart, an ongoing six-year partnership designed to elevate the experience of City Public High School student-athletes and improve academic outcomes through the power of sports.

Under Armour Joins Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Highlights the Importance of Advancing Circularity

Embracing a circular business model is critical to the future of the planet and to the apparel, footwear, and accessories sector. By optimizing resources and working to extend the lifespan of products, companies can accomplish more with fewer inputs – effectively reducing waste and consumption to support people and the environment.

Equality Has No Offseason

At Under Armour, 'Stand for Equality' has always been a core value, meaning we stand with underrepresented groups, such as the LGBTQIA+ community, year-round and remain committed to creating better representation in sport, around the world, and in our own community.

Under Armour Disrupts NYC Market With Innovative New Retail Experience In The Heart of Manhattan

Transcending the typical shopping experience, the UA Flatiron Pop-Up provides a physical manifestation of what Under Armour is all about - creating fearlessly with the courage and conviction to defy convention, innovating by taking bold and smart risks, and showing up big where athletes train, compete, and recover.

To the Greatest of All Time: Tom Brady

A legendary example of the dedication and focused mindset needed to turn a passion into an accomplished career, Tom Brady took a moment to in an emotional beach-side video to let his fans know that he was "retiring for good."

Under Armour Appoints Carolyn Everson and Patrick Whitesell to its Board of Directors

Under Armour, Inc. (NYSE: UA, UAA) today announced the appointment of Carolyn Everson and Patrick Whitesell as members of its Board of Directors effective Feb. 1, 2023. In addition, longtime member Harvey Sanders will retire from Under Armour's Board on March 31, 2023.

UA Elevates the Game to Reach More HBCU Student Athletes Off the Court, Uplift Vision of Black Teammates and Voices of Community Partners

Under Armour believes that the power of sport can unite, inspire, and change the world. We are on a mission to empower the voices of our underrepresented athletes, teammates, and communities in our ongoing effort to Stand for Equality. We continue to celebrate the importance of Black History Month by delivering upon this mission.

An Inside Look At UA Next All-America Week 2023

Back for its 15th year, Under Armour gathered 26 of the best high school volleyball players and top 100+ high school football players in the nation in Orlando, Florida for its annual UA Next All-America Week. Providing a unique mix of world-class experiences and accommodations, access to elite instruction and coaching, and next level competition and exposure for these athletes, the week-long experience provided the next generation of athletes with an opportunity to elevate their mental and physical game.

UA Is Joining Forces with Seth Curry, Jordan Thompson and Fleur Jong to Motivate Athletes to Get ‘Real Tough’ and Achieve Their 2023 Goals

Under Armour is empowering and motivating athletes everywhere to harness that “Real Tough” mindset and level up to their goals this year by teaming up with three UA athletes who know a thing or two about pushing past their limits. Brooklyn guard Seth Curry, gold medalist and volleyball player Jordan Thompson and Netherlands Track & Field para-athlete Fleur Jong, are showing athletes everywhere how they find their “Real Tough” mindset in a series of inspiring content that provides a rare look at the inner mantras that drive them, the physicality of their training and the unwavering dedication they maintain to perform at their best.

Under Armour Announces Stephanie Linnartz as President and CEO

Stephanie Linnartz will join Under Armour as President, Chief Executive Officer, and member of its Board of Directors, effective February 27, 2023.

UA Welcomes The Next Generation Of Athletes No One Saw Coming To Baltimore Headquarters

Today athletes are faced with challenges both on and off the field. Spurred by social media there is more noise than ever and the youth athletes of today are faced with comparisons at every turn. Rising above the noise, the most confident athletes all have one thing in common - they forge their own path to greatness.

Under Armour’s Sharon Lokedi Wins NYC Marathon In Distance Debut

On Sunday, November 6, Sharon Lokedi, of UA Mission Run Dark Sky Distance won the 2022 New York City Marathon wearing a World Athletics-approved prototype of the next iteration of the UA Flow Velociti Elite, with a time of 2:23:23. Traditionally specializing in the 5k, 10k, and half marathon distances, the NYC Marathon was Lokedi’s marathon debut and a celebration of a long journey to compete.

Under Armour Adds Kelsey Plum to its Roster

Kelsey’s new partnership with Under Armour is a perfect alignment of two forces that rally for the underdog and believe in the transformative power of sport.

Introducing UA SlipSpeed, Under Armour’s Most Versatile Training Shoe Designed for Athletes

Under Armour aims to inspire athletes with performance solutions they never knew they needed and now can’t imagine living without. Listening to our athletes and making their problems ours to solve, UA set out to develop a multi-dimensional shoe that can become what the athlete needs it to be exactly when they need it. The result was UA SlipSpeed™ - a performance trainer with a convertible heel design.

Under Armour Sparks Confidence in Young Female Athletes

Hype Headquarters is just one piece of Under Armour’s larger Access to Sport commitment to break down barriers and create opportunities for millions of youth to engage in sport. Through this event and future efforts, the brand has committed to increasing equity in sport by providing more youth athletes with game-changing product solutions. This event kicks off a multi-year initiative designed to help 1,200 young female athletes during its first year.

Coalition Academy